slavic

Slavic New Life

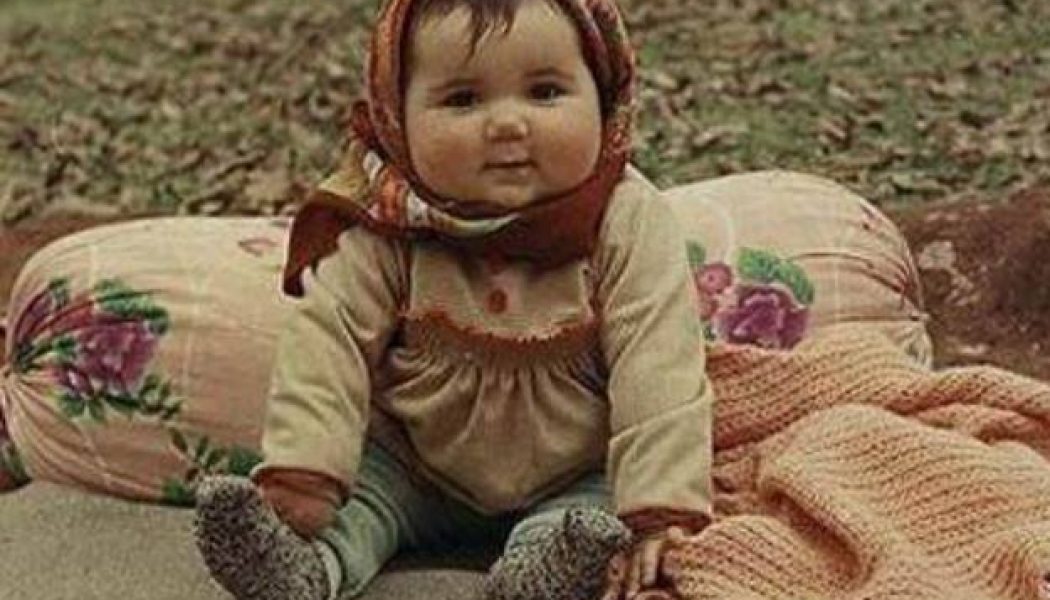

The biggest holiday in a family’s life was the birth of a baby. But a new Slavic soul would have been just as eagerly awaited by demons. For this reason, red ribbons were tied up by the cradle in orde...

Kupalnocka, or the Slavic Valentine’s Day

“Kupała Day was the longest of the year, Kupała Night the shortest – it was one ceaseless passage of joy, song, leaping, and rites,” Józef Ignacy Kraszewski wrote in his Stara baśń (Old Ta...

The Slavic holiday calendar

The Slavic holiday calendar began on 21st December, with a symbolic victory of light over darkness (the Winter Solstice). The Święto Godowe (Nuptial Holidays), also known as Zimowy Staniasłońc would e...