Wheel of the Year

A History Of The Wheel Of The Year

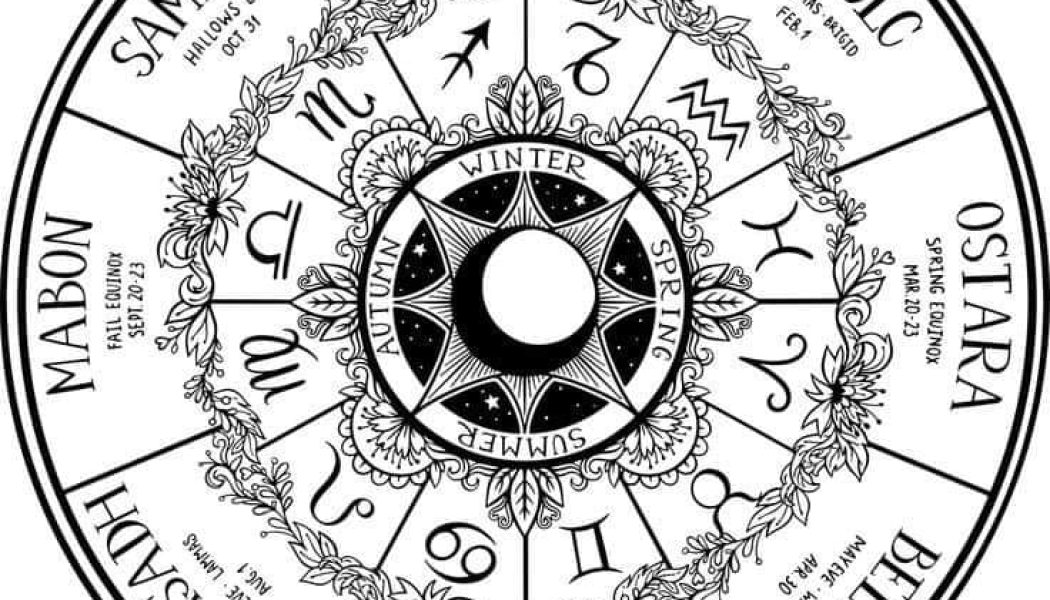

The Wheel of the Year is an ancient concept that has been used by many cultures throughout history to mark the changing seasons and cycles of nature. Its origins can be traced back to prehistoric time...

Origins of the Wheel of the Year: A Brief History of the Pagan Calendar

The Wheel of the Year is a term used to describe the eight festivals celebrated by many modern Pagans. These festivals mark the changing seasons and the cycles of nature. While the Wheel of the Year i...

Solitary Pagans: Understanding the Witches Wheel of the Year

Solitary Pagan witches are practitioners of witchcraft who choose to work alone, rather than as part of a coven or group. One of the most important aspects of their practice is the Wheel of the Year, ...

Solitary Pagan Witches: Celebrating the Solstices Alone

Solitary pagan witches celebrate the solstices as an important part of their spiritual practice. These witches follow a path that is individualistic and self-directed, and they often find solace and c...

Witchcraft Theory & Practice – Solstice and Equinox

The Wheel of Solstice and Equinox is as follows: Winter Solstice (known as Yule); to Spring Equinox (known as Ostara); to Summer Solstice (known as Litha); thence to Autumn Equinox (known as Mabon). T...